Dear friends,

The night before it flooded in New York City, the weathercasters in the area warned their audiences about the potential for more rain than the city’s infrastructure could handle. On the CBS Evening News, for instance, lead weather anchor Lonnie Quinn told his audience, “Quickly rising water is going to be the moniker of this storm, so you gotta take rain seriously.”

Pointing to a map covered in rainfall projections, he added, “It’s showing 4.8 [inches] in New York City. New York has very [little] soil to absorb anything and…the soil that is out there is saturated.” Referencing Hurricanes Ida and Irene, Quinn and others sent explicit warnings to people living in basement apartments and advised them to make sure they had escape plans in place.

What the city’s weather anchors didn’t say, however, is that flooding is intensifying due to climate change, that warmer air holds more moisture, and that, earlier in September, 10 countries and territories had seen devastating, deadly flooding in a span of just 12 days.

Would adding that context have prompted some officials in the area to take added measures to protect New York City’s residents—such as closing schools and shutting down subways to prevent more people from getting stranded in places like airports and train stations? And what if television weather reports integrated climate change into their coverage in a way that helped their viewers better understand the actual stakes—to protect themselves from local disasters, but also to become more literate on the climate crisis writ large?

According to Audrey Cerdan, weather and climate editor at France Televisions, the answer is yes. Earlier this year, the station replaced its traditional weathercast with a weather-climate cast, and it has reached tens of millions of people. I saw Cerdan speak about the transition to a group of journalists and producers at the Climate Changes Everything conference, which was held at Columbia Journalism School in New York just one a week before the flooding.

“In France [the weather report] is still an institution—somewhere between the Eiffel Tower and the baguette,” said Cerdan. “It’s a very popular program that you watch as a family during dinner, one that brings a real service and a service that you want.” But, she added, “It’s 2023, a time when giving the weather without seriously talking about climate change is like covering Wall Street in 2008 without ever talking about the financial crisis.”

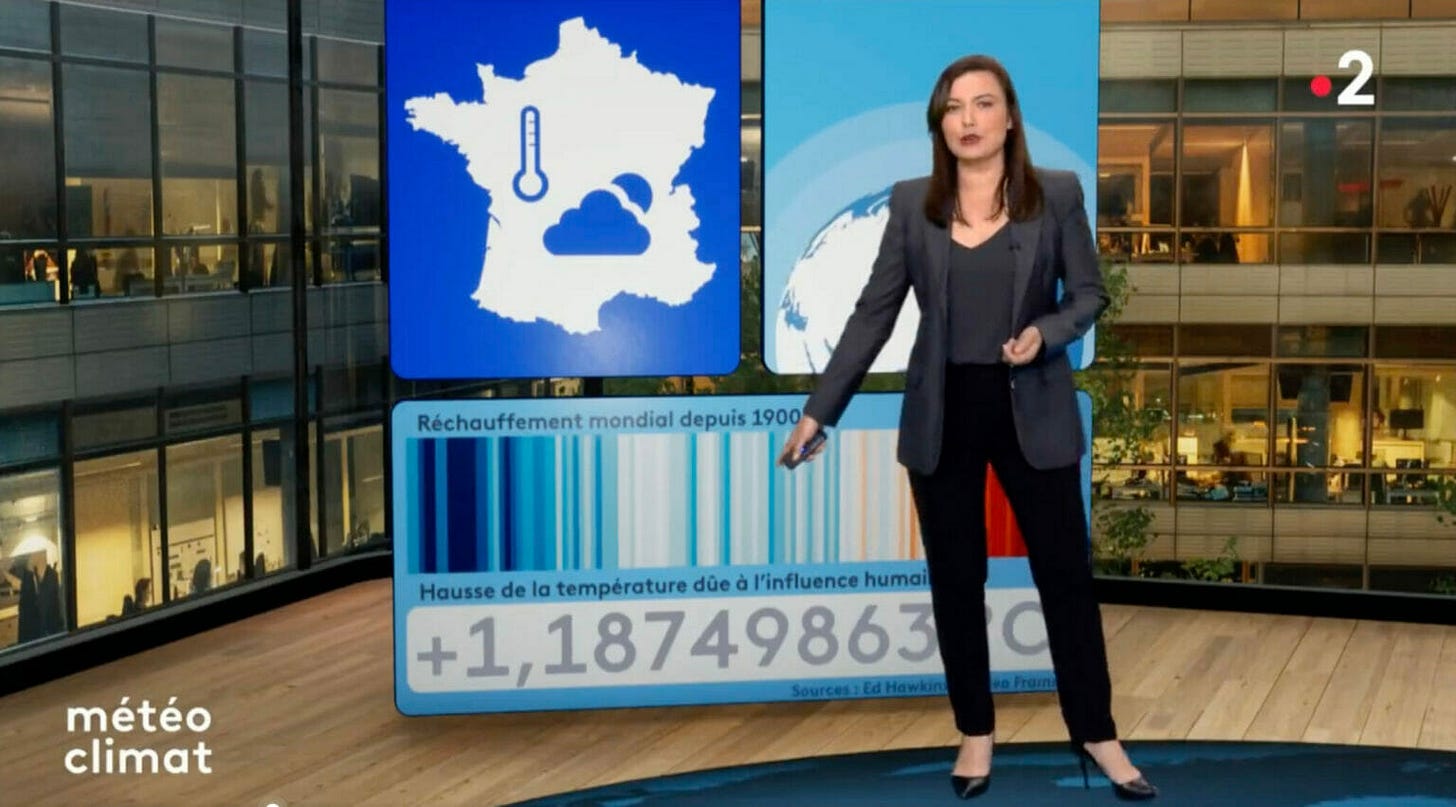

Running on two state-sponsored channels, the segments are only four-minutes long, and their anchor, Anaïs Beydemir, often follows a traditional weather report with short climate explainers and brings on climate scientists to answer questions from the audience. In one recent segment, for instance, a viewer asked: “What percentage of glacier melting is linked to natural evolution and what percent is linked to humans?” In other segments, scientists have responded to questions about record high temperatures and the way climate change has impacted tick populations.

When Cerdan shared segments of the broadcast with the audience in New York, what really struck to me was the set. On a small stage with glass walls, Beydemir often stands in front of a representation of Earth’s climate stripes, a set of colored bars that visually represent the planet’s changes in temperature over the last century, progressing from combination of blues and pinks to an ever-more-solid set of red.

As someone who has those stripes practically painted inside my skull, it was an odd and unexpected relief to see them show up in such a mainstream, public conversation. And yet it’s hard to imagine that happening in the United States, where about one third of the population is still not convinced humans are the cause of climate change and many have never seen the climate stripes. Here, the people most actively working to illustrate the connections between the climate and the weather—people like Eric Holthaus and Daniel Swain—have had to create their own media channels to find audiences.

To be fair, The Weather Channel is more likely to integrate the climate aspect of the story than most news network outlets, and there were a handful of U.S.–based meteorologists at the conference who are working to highlight the climate in longform reporting projects. But it appears that we have a long way to go before climate change is reported as a daily reality, instead of as a set of isolated crises. As Cerdan put it: “The weather is a still image within a much longer movie, which is the climate. You can’t understand the still image if you don’t put it in the context of the movie.”

One of the resounding messages at the conference was that more reporters and media outlets need to be bringing the full heft of the climate story to where people already are. I agree, but I wonder what it would take for climate to start showing up more often in, say, celebrity news or lifestyle coverage—the media’s most popular realms aside from weather.

Yes, celebrities will lose homes to floods and wildfires in the coming years, and we will likely be seeking out more substitutions when we follow recipes. But I’d venture that so much of what people enjoy reading and watching is popular because it allows them to imagine a world without climate change—much like the way television went back to portraying a world free of COVID by 2021, even as the virus was still impacting, and continues to impact, the world we inhabit off the screen.

We know the world is getting warmer and, as a result, the weather will be more extreme and less predictable for the rest of our lives—even if we stop burning fossil fuels tomorrow. But we can’t properly respond to that very real, world-changing problem unless we can see it clearly, in its ever-shifting intricacy. Some of what there is to see is frankly terrifying, but some of it is just the weather. It might feel just short of revolutionary to watch the climate crisis unfold together, rather than having to seek out and make sense of what’s happening in isolation. More mainstreaming of daily coverage could also make it easier to respond collectively.

News you may have missed

New oil and gas drilling

Here we are, living through the hottest year in record, with a new climate catastrophe taking place somewhere on the globe nearly every day. And yet, just a few days after the United Nations General Assembly met to discuss a path away from fossil fuels, the Biden Administration announced a plan to expand oil and gas drilling in the Gulf of Mexico, and the United Kingdom approved the development of the massive Rosebank oil field in the ocean North of Scotland.

Biden’s development plan has reportedly angered both environmental groups and the oil and gas industry, committing to providing three new leases to companies starting new drilling projects in the Gulf over the next five years. It’s a number that seems unconscionable to the many groups fighting for an end to fossil fuel developments, but is also, according to industry spokespeople, an "utter failure for the country."

What’s important to understand about the U.S. development is that last year’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) tied all development of offshore wind to oil and gas development, and even went so far as to set a minimum of three new leases required to start building offshore wind arrays. That provision was added by none other than Senator Joe Manchin (D-West Virginia), the same lawmaker who threatened to block the IRA and ultimately wrote in a pipeline plan for his own home region that has been called a deal with the devil.

But even if Manchin’s IRA stipulation wasn’t in the picture, it’s not entirely clear whether the Biden Administration would have cut the number of new leases down further. While Biden recently gave states more authority to block oil and gas pipelines that run through waterways and launched a U.S. climate corps, he has yet to declare a climate emergency.

Collin Rees, U.S. Program Manager at Oil Change International, pointed out that, “The United States is on track to expand fossil fuel production more than any other country by 2050, which is our most crucial window to limit the impacts of warming.” The cognitive dissonance is enough to leave a person speechless.

Rosebank, on the other hand, is being subsidized by the U.K. government—which claims it has to develop the oil field to bring down energy prices for residents facing “energy poverty” brought on by skyrocketing energy prices. But over £3 billion in tax breaks for the Norwegian oil company behind the deal were “buried in the fine print,” and activists—who have spent the last year pushing hard against Rosebank—are hoping to stop the development on legal grounds. Activists also took to the street on Sunday to voice their disapproval.

Microplastics in clouds (largely coming from your tires)

We know microplastics are present in our waterway, our soil, and all throughout the animal kingdom. But I had never considered their presence in clouds.

According to research conducted in Japan, “Ten million tons of these plastic bits end up in the ocean, released with the ocean spray, and find their way into the atmosphere.” Once they’re there, they get exposed to the sun’s ultraviolet radiation and degrade, adding to warming greenhouse gasses.

And as if there weren’t enough reasons to curb driving, new research has found that particles coming off tires as they wear down is the most prevalent source of microplastics in the ocean.

Walking on (rising) water

Dr. Charlie Gardner, a lecturer at the University of Kent and activist with Extinction Rebellion, is walking 180 miles from Cambridge to Norwich, to highlight the region along the coast of eastern England that will be underwater due to sea level rise by 2050. He’s two-thirds of the way through the walk, and he’s been documenting his journey, which has already been marked by erosion, floods, roads, lost beaches, and plenty of irony. As he passed a golf club located right on the sea, he remarked: “Many of the club members may work in finance, law, media or politics, and be working hard to prolong the fossil fuel age.”

Local mangoes in Italy

Many of Italy’s farmers are struggling with crop failures due to drought, heavy rainfall, and flooding. As a result, they’re beginning to replace crops like wheat, citrus, and wine grapes with mangoes, avocados, papayas, and bananas, and the number of tropical fruit trees there has tripled in the last five years.

“Tropical fruit is the future of Italy’s agriculture; it will save the country from the negative effects of rising temperatures and crazy, wild rainfalls,” one farmer told a British newspaper earlier this summer.

Similar shifts may begin taking place in California, where coffee and banana trees have been making inroads on some farms in the Southern part of the state—but it’s not clear whether water-loving trees from the tropics will survive in an increasingly dry Mediterranean climate.

Saltwater intrusion in New Orleans

As the Mississippi River nears record low levels thanks to ongoing drought, a surge of salt water from the Gulf of Mexico has begun moving upstream toward New Orleans prompting the declaration of a national emergency. When it arrives later in October, it threatens to inundate the water supply in several of the city’s parishes, polluting drinking water and corroding pipes that likely contain lead. Even if rain arrives soon—and there’s no clear sign that it will—experts say salt could remain in the city’s drinking water into 2024.

And because I’m an agriculture nerd, I can’t help but think about the soil in the greater Mississippi basin, much of which is degraded and absorbs/holds very little of the water that passes through it after decades of conventional monocrop corn and soy production. When that happens, the water that does move through the system tends to travel down quickly in the winter and spring, leaving an increasingly empty river in the drier months.

Opposition to wind energy is “energy privilege”

A group of scientists combed through the data on opposition to wind farms in the U.S. and Canada and found that it has grown significantly in recent years. Around 10 percent of wind projects were opposed in the early 2000s, and now around 25 percent face some kind of push back. The researchers found that opposition was associated with both whiteness (in the U.S.) and wealth (in Canada), and concluded: “When wealthier, Whiter communities oppose wind projects, this slows down the transition away from fossil fuel projects in poorer communities and communities of color, an environmental injustice we call ‘energy privilege.’”

On the brighter side

1. A Jaguar was caught on wildlife camera in the Arizona mountains for the second time this year. “These photos show that despite so many obstacles, jaguars continue to reestablish territory in the United States,” said Russ McSpadden, a conservation advocate at the Center for Biological Diversity. “This is a wonderful reminder that these big cats move great distances across the landscape. It drives home the importance of protecting connected habitat for these elusive, beautiful felines.”

2. Six young people in Portugal have filed lawsuits against 32 governments in and around the European Union for failing to reduce emissions in time to limit warming to 1.5 C. The case is the first like it to be filed at the European Court of Human Rights, and it could set an important legal precedent in the region.

3. Indigenous Mi’kmaq communities and marine biologists are partnering to protect and expand beds of eel grass, a key aquatic species that helps lock carbon into ocean sediment as it grows.

4. A law passed in Panama giving leatherback sea turtles legal rights provides an entry point to this deep dive into the rise of similar laws around the globe, which are part of the growing Rights of Nature movement. Designed to protect plants and animals from becoming threatened or endangered, these new laws are used to enlist "stewards to preserve habitats and restore animal populations—and when animals are threatened, [file] lawsuits on their behalf." The movement, which is being championed by a growing coalition of Indigenous peoples and their allies, and was a reoccurring theme during New York Climate Week, is one of the more hopeful developments I've seen in the face of the interwoven climate and biodiversity crises.

The Visual

Javelinas stealing pumpkins in Arizona, photo by Russ McSpadden.

Take care,

Twilight

I love the idea of integrating climate change context into the weather report and more pop culture generally. We can’t expect everyone to seek it out given the stresses of daily life, even as we need everyone to learn more about it.

Great idea mentioning climate with weather!