The Undeniable Magic of Undisturbed Soil

Scientist Liz Koziol on fungi, grasslands, and the place where they overlap.

Dear friends,

I love learning from people like Liz Koziol. She’s a research scientist at the University of Kansas focused on the fungi that connects plants to soil, or arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF)—and when she talks about this little known, underappreciated part of the natural world, she lights right up. I do too, it turns out.

Unlike fungi that fruit above ground (i.e. mushrooms), mycorrhizal fungi live their whole lives underground, where they play a key role helping plants thrive in a changing climate. Koziol has been working to help restore prairieland in Kansas and she also runs a business selling a granular form of mycorrhizal inocula to farmers, gardeners, and landowners. (And, in case you’re wondering, this is not a sponsored post.)

Here’s an excerpt from our conversation.

How did you get into working with soil fungi in tallgrass prairie ecosystems?

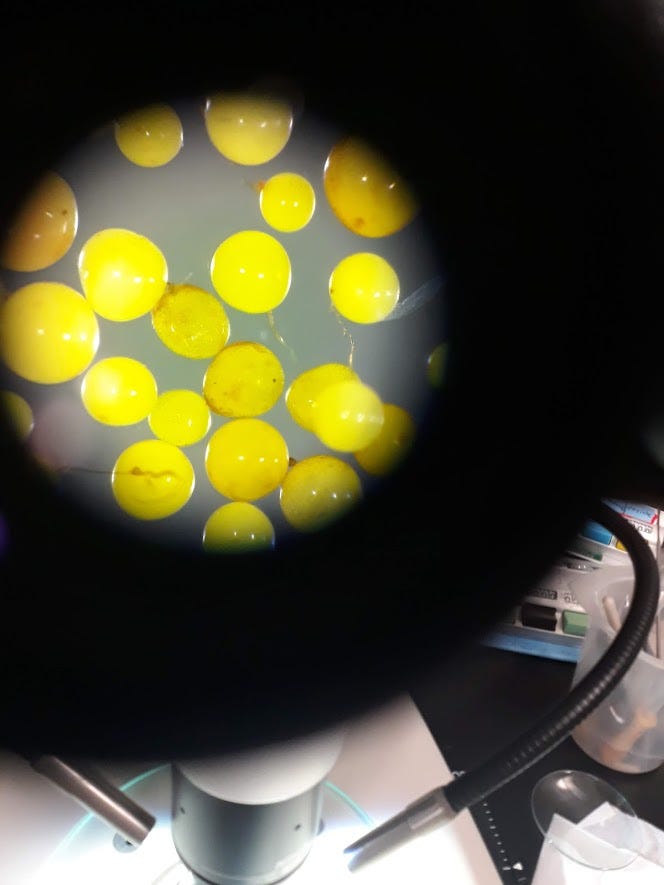

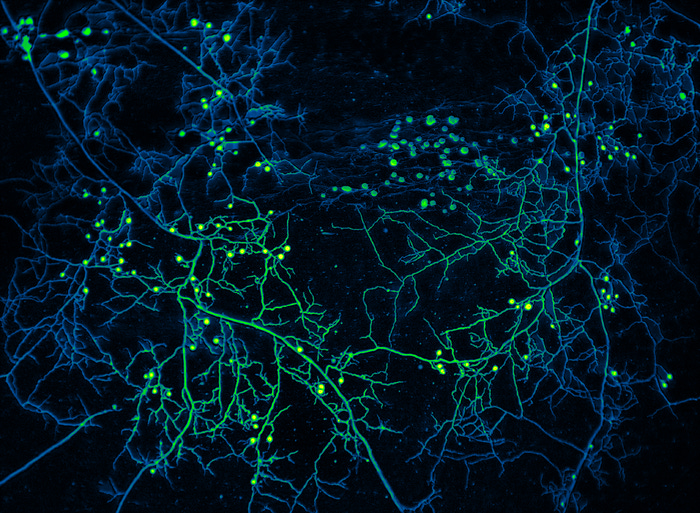

It was dumb luck. I had no idea that arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi even existed until I took a job as an hourly assistant in a laboratory right after college. AMF is the fungi that dominates the globe, about 85% of land plants associate with these fungi. And I just fell in love with them—culturing them and looking at them under the microscope. They're beautiful! Despite the fact that they spend their entire life cycles below ground, when we light them up under a microscope they have all these unique colors and some of them look like crystal balls.

I also quickly saw their power in action. One of the first projects I worked on was with a botanist named Elizabeth Middleton. She ran experiments in the Kankakee Sands Prairie, where she inoculated [prairie] restoration plots with soil from an old growth prairie and then looked at how the plants responded. You could see the difference it made with the naked eye; some of the plants responded massively with just a little bit of soil inocula. Species like baptisia [a wild pea] grew to be over a meter wide when they had these microbes.

Can you say more about the research you’re doing now?

I’ve continued to work with soil transplants from old growth prairies, and when we've isolated the fungi and transplanted just that material into restoration plots, we’ve seen the same effect [as soil]. And now that we know which microbe is driving the plants’ response, we can harness it as a tool for restoration. A lot of my experiments ask questions like: How much [native AMF] do we need to put out there? Is it best to do it with nurse plants? Or can we broadcast it and till it in? The end goal for me is to [create] a tool that land managers can use to make their restorations better and more diverse.

You're working in a region that is covered with monoculture agriculture—corn, soy, wheat. How much native prairie remains?

Where I grew up, in Northwest Indiana, at the far eastern edge of the prairie, it is so massively disturbed. All those landscapes were converted to row crop agriculture, and the few remaining pockets of prairie tend to be really tiny. One of the prairies we’ve visited is along a rail line, a space that would not have been historically dug up to put crops in. So we have these long tracks of native prairies that have never been plowed, but they're only like 10 meters wide. Another example is cemetery prairies. In the past, a small plot, two to five acres, would be set aside for a cemetery, and these patches would experience some disturbance if someone died. But otherwise, they are undisturbed pockets of land. And they are some of our only windows to see what an old growth prairie would look like.

Where I live now, near the Flint Hills in Central Kansas, there is more intact prairie. It wasn’t plowed under because it's so rocky here. But much of the existing prairie here has been degraded by overgrazing. It's estimated that only about 4% of the historic prairie remains, but I would guess it's much lower, because many of the existing areas we have are still being overgrazed.

What, in your experience, makes the tallgrass prairie such a special ecosystem?

Prairies are stunningly gorgeous. And they are so diverse from a plant perspective. You can take one large step in some of these prairies and cross over 27 different plant species, sometimes more. We call them grasslands, but these communities have many types of plants, including pollinator species such as milkweeds, wildflowers, and legumes.

And they’re maintained by fire. Historically, the whole central region of the U.S, most of this grassland range, would have been maintained by Native peoples using fire to knock back trees and make the space better for grazing for bison and other ungulates. The prairies are still maintained by fire. Some people call it a “disturbance,” but it's a necessary part of the system.

Grasslands hold about one third of terrestrial carbon on the planet. But those benefits are not visible to most of us. Will you say more about how intact prairies help fight climate change?

Most people don’t think of grasslands the way they do forests. You can walk through them, and they’re lush and green, and there are some beautiful bugs. But much of the action of the prairie is actually happening below ground. Prairie plants are very long- lived; some of them live for decades. And the plants have perennial root systems that can go down 10 meters [over 32 feet] into the soil. These roots move carbon from above ground down into long-term storage. And because these ecosystems are so diverse, the plants all have different kinds of root architectures, so they take up many pockets in the soil and fill it up with carbon.

Diverse prairies are also super drought resilient because the plants have these long tap roots [that can dig down very far to access moisture]. So even if it's a terribly dry year, they can bounce back the next year and still be a flourishing community. I think fungi have an important role in both our restorations and our agricultural systems in terms of making them more resilient.

How exactly does arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi help those roots get developed in places where you're restoring prairie?

Fungi are excellent at acquiring micronutrients from the soil. AMF are great at acquiring inorganic phosphorus. Prairie plants have adapted to use the fungi to get into those fine soil pockets and collect nutrients for them. AMF make a massive difference in how well these plants establish themselves and even help decide which plants can get established. Some are unlikely to germinate from seed unless they have the right fungi there.

I've done some reporting on the no-till agriculture movement, which is designed to help soil fungi get re-established in farm fields. And yet a lot of those farmers also use herbicide to control weeds when they stop tilling. What are your thoughts on no-till?

No-till has done wonders in terms of keeping our soil from washing away into our water systems, and that's amazing. We have a photo in our lab and of one of our lab leads, Peggy Schultz, with one foot in a prairie and another foot in an ag field, which is like 20 inches lower because so much of it has washed away. [Soil erosion on farms] is a crying shame. But yes, also with no-till you usually have glyphosate use and other chemical applications. There hasn't been a lot of direct research into how these chemicals affect mycorrhizae, but some studies have shown that their application can make spores less viable. And so it doesn't seem great for the fungi. But what’s even worse for the fungi is the fact that on many farms the fields sit empty for at least part of the year. AMF are dependent on plants to survive; they can't fix their own carbon and have to be fed sugars from a plant host. And so in areas where you have a lot of brown fields [i.e. no cover crops growing in fall in winter], their health can decline.

That makes sense. I’d heard a number of soil scientists talk about the importance of keeping “roots in the ground” all year round.

There were long-lived perennial root structures in the prairie for hundreds of years. So AMF have evolved to expect that. If you’re growing a plant like corn, which has very shallow roots, and then you leave the field bare half the time, the population of AMF is really affected. In places where we do active transport of the mycorrhizae from the old growth prairie, we've harmed these fungi so much that they hardly function.

What do you think it will take for more people to begin appreciating native grasslands and recognizing them as key to getting through this next phase of climate disturbance?

I think some of the great success stories in the prairie have happened when we have an obvious champion to point to. One that is a focus of research here at the University of Kansas is the monarch butterfly. Monarchs depend on milkweeds, so in trying to save this butterfly, people started to care about milkweeds, and milkweed habitat, which is a native grassland. And so there have been lots of grassland restoration projects focused on pollinator health in recent years. I think that's interesting, and I'm excited that people can have something to look to as an example, even though there are a million other similar, fascinating examples of [interdependent relationships] in the prairie.

There is also the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve in Kansas but it's not as attractive to most visitors as, say, geysers or mountains. It's just acres and acres of rolling hills. It takes a trained eye to be able to appreciate the beauty of the prairie.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Climate news you might have missed

A heat pump wave is heading to California

I wrote a short article for the San Francisco Chronicle about several efforts underway to electrify low-income people’s homes in California. The TLDR version: The state is incentivizing heat pumps in a big way, but not everyone can buy them outright, nor has the time to research how. Now, a whole host of pilot projects are jumping into the space to install heat pump HVAC systems and hot water heaters directly in low-income people’s homes for them. And the race is on because starting in 2027 the Bay Area will begin requiring everyone to replace broken appliances with heat pumps.

One big takeaway (and I have many after spending the last six months drilling down to learn all I can about home electrification) is that this change is happening whether we like it or not. California has committed to installing 6 million heat pumps in homes by 2030 so if you’re considering investing in gas appliances you may want to think twice.

Can universal basic income protect the Amazon?

An estimated 20 percent of the Amazon rainforest has now been razed, and that loss has led to a whole host of other tipping points within the ecosystem, including record-level drought and a dramatic increase in fires.

I was interested to read about an experiment being undertaken by climate action NGO, Cool Earth and two Indigenous-led organizations, that is offering families in Central Peru £2 a day with no strings attached in hopes that the boost in income may help reduce deforestation.

Here in the U.S., universal basic income (UBI) pilot programs have been shown to work well in addressing a myriad of social problems. They’ve helped low-income people pay off debt, access new transportation options, feed their families, and get the medical care they need. They’ve also often led the recipients to pursue education, step out of cycles of domestic abuse, and rethink their goals.

But they’re also always temporary—or they have been so far.

According to The Guardian, the pilot in Peru is based on the theory that more financial security will lead communities to hold onto forested land rather than selling or developing it to survive.

“When people are in urgent need and want to take their children for medical care or to school, sometimes these cycles of poverty lead them to take on roles [in the drug trade], or to sell their land or allow their trees to be cut down,” Isabel Felandro, the global head of programs for Cool Earth, told The Guardian.

In addition to paying for their basic needs, Felandro added: “some people are already buying seeds and investing in reforestation—they worry about droughts, so they’re reforesting around the spring to maintain their water supply—a communal activity.” Like the pilots we’ve seen here in the U.S. the one in Peru will only last two years; a virtual blip in the life of an ancient forest. We can only hope those in power in Peru, and elsewhere, will heed the lessons it offers.

Planning the solar gold rush

Keeping up with all the new solar farms planned in the American West can be a J.O.B. For that reason, I really appreciated Jonathan Thompson’s latest rundown of the Bureau of Land Management’s updated Western Solar Plan. The plan will make 31 million acres (the equivalent of 130 Las Vegases) across eleven states available for new solar development in the coming years. It is being hailed by some as a win-win because while it will give the solar industry a great deal of flexibility about where they build new arrays, it also protects many sensitive and protected landscapes and habitats. However, Thompson also points to critics who say the plan will lead to, “a sprawling hodgepodge of massive solar installations scattered across the desert rather than all concentrated in a few places.”

The plan assumes that rooftop solar will remain a relatively small piece of the puzzle, and that appears the be the case, given the lack of strong incentives and rebates for homeowners. But I’m consistently surprised that we haven’t done more to incentivize solar on the millions of acres of warehouses still being built in the West to support the shipping industry.

Changing how wealthy nations eat

We know that diets rich in meat and dairy result in more greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, but a new study takes that information further by looking at the links between climate-warming foods and global wealth.

The study, published in Nature Climate Change, looked at what would happen if more people ate according to the EAT-Lancet Planetary Health Diet, which prioritizes plant-based food without entirely restricting meat and dairy, and found that for those of us in the so-called developed world, even moderate shifts in that direction can have a sizable impact. According to Anthropocene Magazine:

Most interestingly, the researchers calculated that if the highest-earning, ‘over-consuming’ population groups—which make up 57% of the global population—changed their diets, that would cut back 32% of global dietary emissions. That is more than enough to offset the 15% increase that would be required to bring poorer populations in line with the recommended global diet.

Undoubtedly, dietary change on this global scale would be hard to achieve: it would require an 81% decrease in the global supply of red meat and a 50% reduction in grain, while the supply of legumes and nuts would need to shoot up by 438%, and fruit and vegetables by 28%.

But this study identifies buying power as a critical lever to try and achieve this goal. There could be great promise, its researchers suggest, in nudging the habits of wealthy consumers via eco-labelling, carbon taxes on diary and meat, and expanding the availability of vegetarian alternatives.

Can we climate-proof ketchup?

I’m always tracking the impact of climate change on our food system, so I was interested to read about the way the tomatoes used in Heinz ketchup have struggled in this year’s prolonged California heat.

Zach Bagley, managing director of the California Tomato Research Institute, told the San Jose Mercury News that this year’s harvest could be cut by as much as 20 percent due to the impact of high temperatures on the plants’ flowers.

The company is working to engineer drought and heat-tolerant tomato plants quickly and farmers have already been making adjustments. One of Heinz’s large-scale growers told the Mercury News it, “buries their irrigation systems deep in the soil to encourage the roots to find the water,” and sprays the leaves with a clay polymer to protect them from the sun.” Ultimately the company is prepared to source tomatoes from other places, but it’s not clear that any of those places—Florida? Mexico?—will hold up any better over the long term.

The pushback

The UK government will not fight a legal challenge against the decision to grant consent to drill in the Rosebank oil field, off the Shetland Island in the North Sea and a second field to the south, called Jackdaw. The oil companies involved, Shell and Equinor, may still challenge the decision. And the company’s licenses haven’t been withdrawn. But activists in Europe—who have been opposing Rosebank very vocally for the last few years—see this as a pivotal moment. They gathered outside Parliament earlier this week make their voices heard.

On the brighter side

1. In this video, a group of Indigenous young people from several Nuu-chah-nulth nations in Vancouver Island, BC are shown learning to harvest crabs and sea urchins according to traditional ways.

2. This summer’s Park Fire has been extremely destructive. But Don Hankins, a renowned Miwkoʔ (Plains Miwok) cultural fire practitioner, also says he sees signs of beneficial changes to the land as well.

3. In several European cities, Tara Grescoe reports, trains and trams run over lawns, rather than cement. In a recent thread, he wrote “2 kms of track creates 1.5 football fields' worth of green space, reducing air pollution and urban heat island effect.

4. In late August, the California Senate approved The Room to Roam Act, a bill that would provide more wildlife corridors and other points of connectivity to make it easier for animals to move freely across the state. Now the bill awaits Governor Newsom’s signature.

Take care and keep going,

Twilight

Nice. Especially importance of cover crops!

Fascinating story about the importance of fungi, and nice news updates.